Good pictures

Good picturesIn a few hours, a spaceship should blast off from Florida to search for signs of aliens.

Its target is Europa, a deeply mysterious moon orbiting the distant planet Jupiter.

Trapped under its icy surface, it could be a vast ocean with twice the volume of water on Earth.

The Europa Clipper spacecraft will chase a Europa mission that left last year, but using a cosmic piggyback, it will overtake and arrive first.

It won’t be until 2030, but its discovery could change what we know about life in our solar system.

The moon is five times brighter than our moon

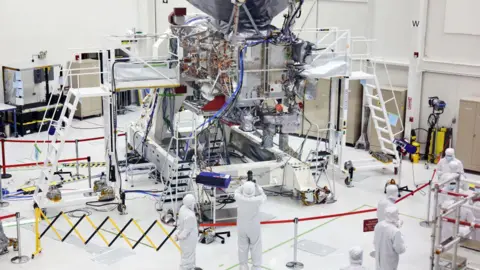

Years in the making, the launch of the Europa Clipper was delayed at the last minute after Hurricane Milton hit Florida this week.

The spacecraft rushed home for shelter, but after checking the launch pad at Cape Canaveral for damage, engineers have now given the go-ahead for lift-off at 1206 local time (1706 BST) on October 14.

“If we find life far from the Sun, it could mean a separate life for Earth,” said Mark Fox-Powell, a planetary microbiologist at the Open University.

“This is very significant because if this happens twice in our solar system, it means that life is very common,” he says.

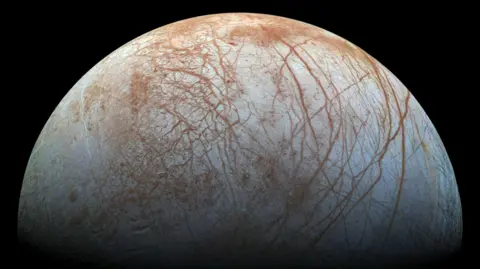

At 628m from Earth, Europa is slightly larger than our moon, but that’s where the similarities end.

If it were in our sky, it would shine five times brighter because the water ice would reflect more sunlight.

Its icy crust is up to 25 kilometers thick, and, sloping down, may be a large saltwater ocean. There may also be chemicals that are raw materials for simple life.

Scientists first realized that Europa might support life in the 1970s when they spotted water ice while peering through a telescope in Arizona.

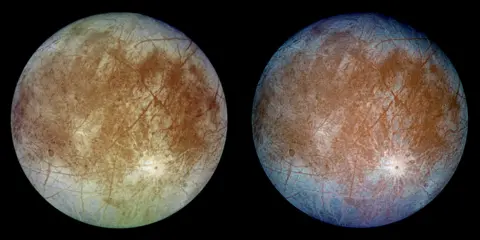

The Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft took the first close-up images, and then in 1995 NASA’s Galileo spacecraft flew past Europa to take some deeply enigmatic images. They showed a surface full of dark, reddish-brown cracks; Fractures with life-supporting salts and sulfur compounds.

The James Webb telescope captured images of what appear to be plumes of ejected water 100 miles (160 kilometers) above the moon’s surface.

But none of those missions got close enough to really understand Europa.

Water flies through the worms

Now scientists hope that instruments aboard NASA’s Clipper spacecraft will map nearly the entire moon, as well as collect dust particles and fly through water plumes.

Brittney Schmidt, an associate professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at Cornell University in the US, helped design the laser that looks through the ice.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute“I am very excited to understand Europe’s plumbing. where is the water Europa has an ice version of Earth’s subduction zones, magma chambers and tectonics – we’re going to look at those areas and try to map them,” he says.

His instrument, called Reason, was tested in Antarctica.

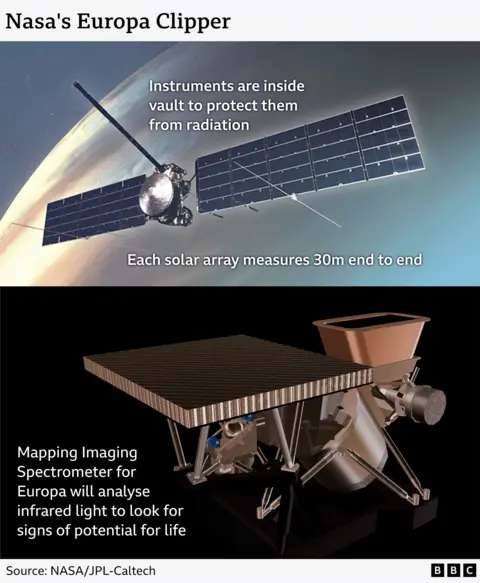

But unlike Earth, all the instruments on Clipper will be exposed to large amounts of radiation, which Prof Schmidt says is “a big concern”.

The spacecraft will fly past Europa about 50 times, and each time it will be blasted with radiation equivalent to a million X-rays.

“Most electronics are in a vault, heavily shielded to prevent radiation,” explains Professor Schmidt.

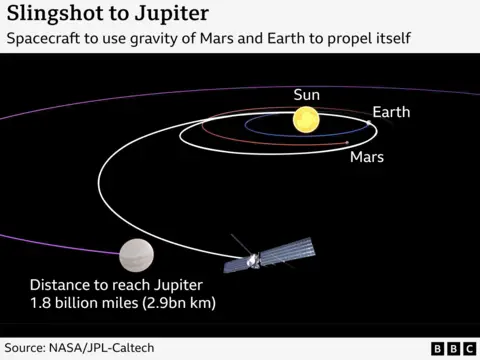

The spacecraft is the largest ever built to visit a planet and has the longest journey. Traveling 1.8 billion miles, it orbits both Earth and Mars, causing the so-called sling-shot effect further toward Jupiter.

It can’t carry enough fuel to run on its own, so it would resist Earth’s speed and Mars’ gravity.

It will overtake the European Space Agency’s spacecraft Zeus, which will fly by Jupiter’s other moon Ganymede on its way to Europa.

When Clipper approaches Europa in 2030, it will restart its engines to carefully maneuver itself into the correct orbit.

NASA/JPL/DLR

NASA/JPL/DLRAstronauts are very cautious when talking about the chances of finding life—they don’t expect to find human-like creatures or animals.

“We’re looking for the possibility of life, and you need four things – liquid water, a heat source and organic matter. And finally, those three things have to be stable for a long time so that something can happen,” explains Michael Dougherty, professor of space physics at Imperial College London.

And they believe that if they can better understand the ice surface, they will know where to land a craft on a future mission.

An international team of scientists from NASA, the Jet Propulsion Lab and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory will oversee Odyssey.

At a time when there’s a space launch every week, this mission promises something different, suggests Professor Fox-Powell.

“There’s no profit. It’s about exploration and curiosity, and pushing back the boundaries of our knowledge about our place in the universe,” he says.

“Friend of animals everywhere. Devoted analyst. Total alcohol scholar. Infuriatingly humble food trailblazer.”